Explore Missouri’s Digital History

Missouri has long demonstrated an unwavering commitment to preserving its rich history through various initiatives, notably the Local Records Preservation Program and the Missouri Digital Heritage website. By providing expert guidance, funding, and advanced conservation services, the state ensures that invaluable records are meticulously managed and accessible to future generations. These efforts reflect Missouri’s dedication […]

When It Comes to Preservation, the Time Is Now

National Historic Preservation Month is a time to reflect on the importance of preserving our shared heritage. Throughout May, communities across the nation engage in activities that highlight the significance of safeguarding historical sites, artifacts, and stories. These grand efforts undoubtedly make substantial changes, protecting the physical and cultural landscapes that define our collective identity. […]

Impetus for Action: Anna’s Story

By Farica Chang, Managing Principal Our client, Anna, created a powerful video to share with others on the importance of digitizing your family memories before it’s too late. We’re always grateful to learn about the impact our work has in protecting legacy, and we’re blown away when our clients take the time to create messages […]

Building on the Busch Family Legacy

Anyone familiar with St. Louis’s history knows the impact the Busch family has on this region. Grant’s Farm, Busch Stadium, and the Anheuser-Busch Clydesdales are some of the hallmarks of living under the Arch’s shadow, and St. Louis wouldn’t be the same without this historical family’s influence. However, when family legacies get distilled into the […]

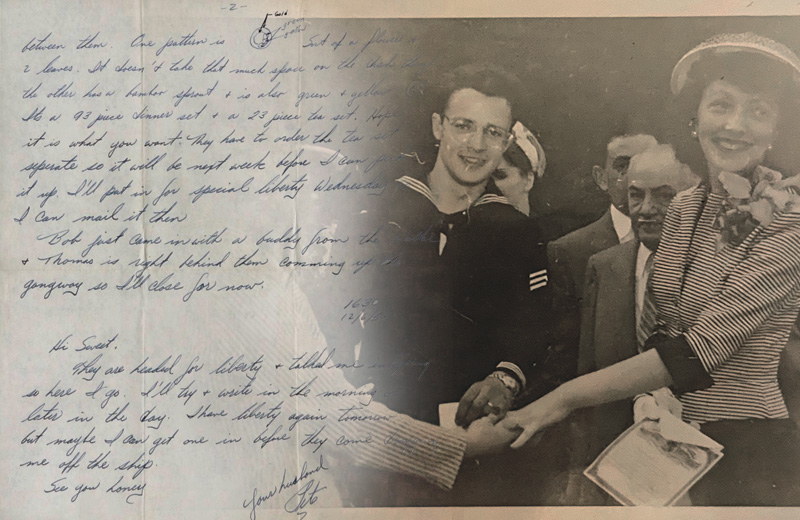

[Watch] A Legacy of Love – Getting Started

https://vimeo.com/946624707/0fcb79fc4f In this clip from our webinar, A Legacy of Love: Digitized Letters Bridge Generations, guest Rosemary Cassie explains the emotional core this collection of letters holds for her family, especially after her mother passed away in early 2020. Making sure the letters were available to the family and using them to maintain connection were two […]

ROT and Prioritizing Materials for Digitization

When planning to digitize a collection, it’s important to suppress the urge to jump right in and scan everything. Not all items are created equal; some may be more fragile or rare, while others may have greater historical or cultural significance. Prioritizing the materials in your collection can help you achieve your goals effectively and […]

Anderson Archival Joins Digital Stewardship Association

By Farica Chang, Managing Principal Anderson Archival continues our focus on digital preservation by becoming a member of the prestigious National Digital Stewardship Association (NDSA) in March 2024. This move marks a pivotal moment for us as we now join other esteemed members of the association to actively engage in shaping the future of digital […]

The Dow Foundation Archives: Cultivating Historical Context

Archivists are often eager to illustrate the one-of-a-kind perspective their collection presents. Artifacts like postcards, candid photos, and personal correspondence offer a way to tell previously untold stories about our origins. However, historical archives not only provide a peek into the past, but they also offer new context around the histories we think we know. […]

[Watch] Preserving Family Legacy Through Digitization

In this portion of our latest webinar, Protecting Family Legacy Through Digitization: A Conversation, Director of Operations Hadley Grow talks with Anderson Archival client Kelly Donovan about how her collection came to be digitized. If video isn’t for you, the transcript for this portion of the talk is below. To view the full webinar and transcript, […]

What Is Metadata?

In our data-driven society, metadata has become a frequently used term, but do you know what it actually is? The process of weeding out the differences between data and metadata can be confusing. Bruce Schneier explains it best in his book Data and Goliath, “Data is content, and metadata is context.” Think about the photos […]