Building on the Busch Family Legacy

Anyone familiar with St. Louis’s history knows the impact the Busch family has on this region. Grant’s Farm, Busch Stadium, and the Anheuser-Busch Clydesdales are some of the hallmarks of living under the Arch’s shadow, and St. Louis wouldn’t be the same without this historical family’s influence. However, when family legacies get distilled into the […]

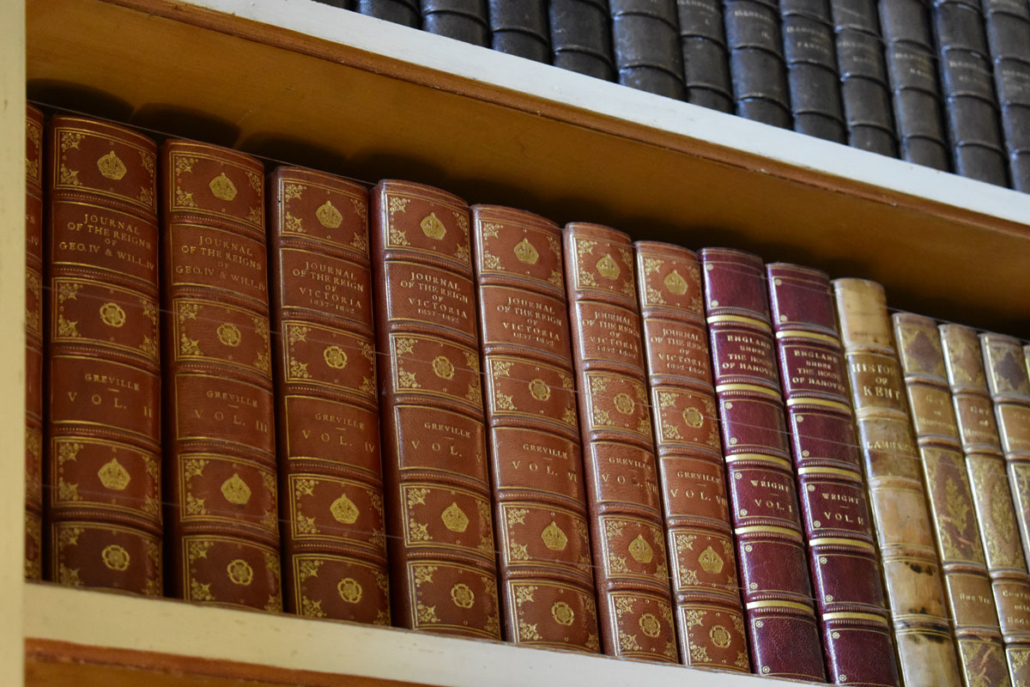

The Dow Foundation Archives: Cultivating Historical Context

Archivists are often eager to illustrate the one-of-a-kind perspective their collection presents. Artifacts like postcards, candid photos, and personal correspondence offer a way to tell previously untold stories about our origins. However, historical archives not only provide a peek into the past, but they also offer new context around the histories we think we know. […]

What Is Metadata?

In our data-driven society, metadata has become a frequently used term, but do you know what it actually is? The process of weeding out the differences between data and metadata can be confusing. Bruce Schneier explains it best in his book Data and Goliath, “Data is content, and metadata is context.” Think about the photos […]

Finding Harmony in the Past

Imagine discovering boxes of your loved one’s manuscripts and documents you never knew about until after they passed. Going through a late loved one’s belongings can be a daunting and emotional task. It stirs up memories and feelings long forgotten. Finding items you never knew about, like boxes filled with a life’s journey on paper, […]

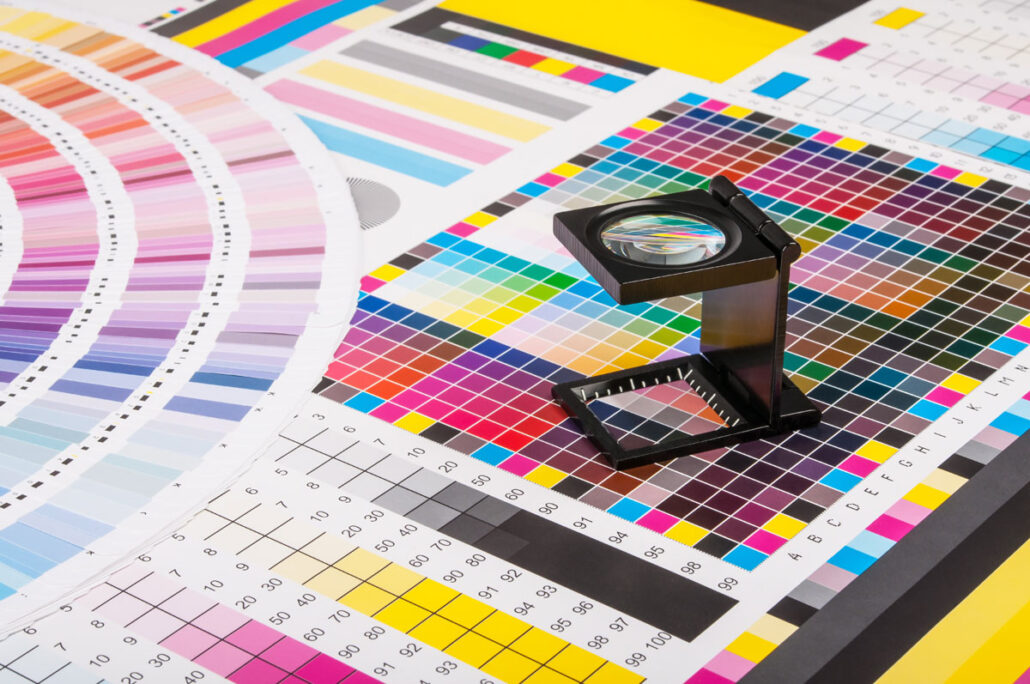

Reduce, Reuse, ReFADGI: Updates to FADGI Standards for 2023

By Archives Technician Shana Scott Every industry has its own “language” or commonly understood terminology and shorthand to expedite communication. If you’ve ever overheard a business call in the airport or watched baristas signal to each other to help one another when service gets hectic, then you’ve probably seen this in action. The archival community […]

Digitization Standards and Practices

By Archives Technician Shana Scott What value does an archive or historical collection provide if it can’t be shared? Access and useability help bring a collection to life, allowing visitors and patrons to discover history that otherwise would be lost to them. But how do you provide that access and sharing while still preserving and […]

Experience Stories Worth Celebrating

By Operations Manager Marcia Spicer Regardless of the audience, every museum, historical society, or specialized library knows they have a story worth telling. That’s why they’ve taken countless hours, dollars, and coordinated effort to form. In collections, we often see decades of dedication and work spearheaded by a single individual or a small group who […]

Access to Your Archive: Make It Easy, Make a Difference

Why digitize? This is the question many archive owners, collectors, and curators face. In an increasingly digital world, analog access to collections and archives is still the norm. But should it be? A Philosophical Question If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? […]

Learn: Digital Preservation vs. Digitization

It may feel like the terms “digital preservation” and “digitization” are interchangeable, but it’s better to think of them as fingers and thumbs. All thumbs may be fingers, but not all fingers are thumbs. Digitization is the thumb and digital preservation are the fingers. Digitization is necessary to the overall function of digital preservation, but […]

Learn: What is a Digital Collection or Digital Library?

Whether you’re a researcher, student, librarian, or bibliophile, it’s likely you’ve accessed a digital collection or enjoyed a digital library. Using these convenient resources may lead you to wonder how to make your own collection sharable online. Learn about the concepts of digital collections and digital libraries in this Anderson Archival explainer. What Is a […]