Digitization is not done in a vacuum. Many items are too damaged or fragile to undergo digitization without conservation.”

—Noah Smutz, NS Conservation

Around a year ago Anderson Archival had the pleasure of discovering Noah Smutz of NS Conservation. In searching for a physical conservation solution, we learned about the work Smutz does right here in St. Louis.

NS Conservation and Anderson Archival may initially seem like unlikely partners, or even competition in the field of document preservation, but digitization and conservation often work hand in hand. For collectors who desire the most comprehensive preservation of their item, both are necessary.

From initial conversations to the current partnership between our two businesses, it was always clear that Smutz loves the work he does. He also understands and embraces the importance of digitization to the conservation world. After all, he says, “it’s a lot harder to use the find function on a book than a PDF.”

Smutz grew up in the Midwest and frequently spent time with relatives in the St. Louis area. Smutz met his future wife, Sophie Barbisan, in Washington, D.C., while doing conservation work for different branches of the Smithsonian. Barbisan was hired by the St. Louis Art Museum in August of 2018 as their paper conservator. Smutz followed in April 2019 and St. Louis became the home for NS Conservation.

Smutz describes his path to book conservation as a winding one. Initially interested in the field of archaeology, Smutz traveled to a dig site in Crete as an undergrad. There, the heavy toll of spending hours in the sun, and a future of potentially spending months away from family, made him understand that archaeology wasn’t right for him. But that trip introduced him to archaeological object conservators, professionals who worked near the dig to stabilize discovered objects.

Once back in the US, Smutz began working for the University of Kansas Libraries, conserving circulating collections. This opened up a new field of study, one that combined a love for history with the practice of conserving books. Over the past few decades book conservation has becoming increasingly entwined with digitization. “Every internship and job I’ve held since I’ve entered conservation in 2011 has involved doing conservation work to allow for digitization,” Smutz explains.

As a Professional Associate of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC), Smutz holds to their code of ethics. A conservator does no more to an object than is required to preserve it. This is the difference between conservation and restoration. Restoration is the attempt to make the book appear new. As a conservator, Smutz says, “I’m not trying to hide that the book has lived a life. I’m just trying to make it usable and safe going forward.”

The Family Bible

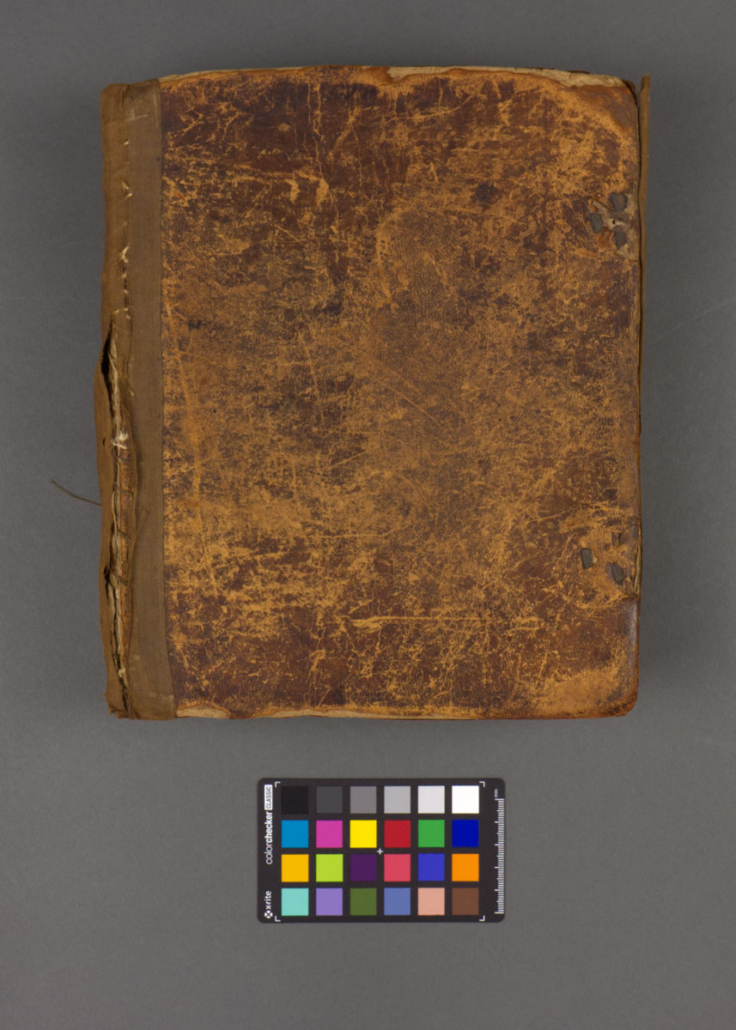

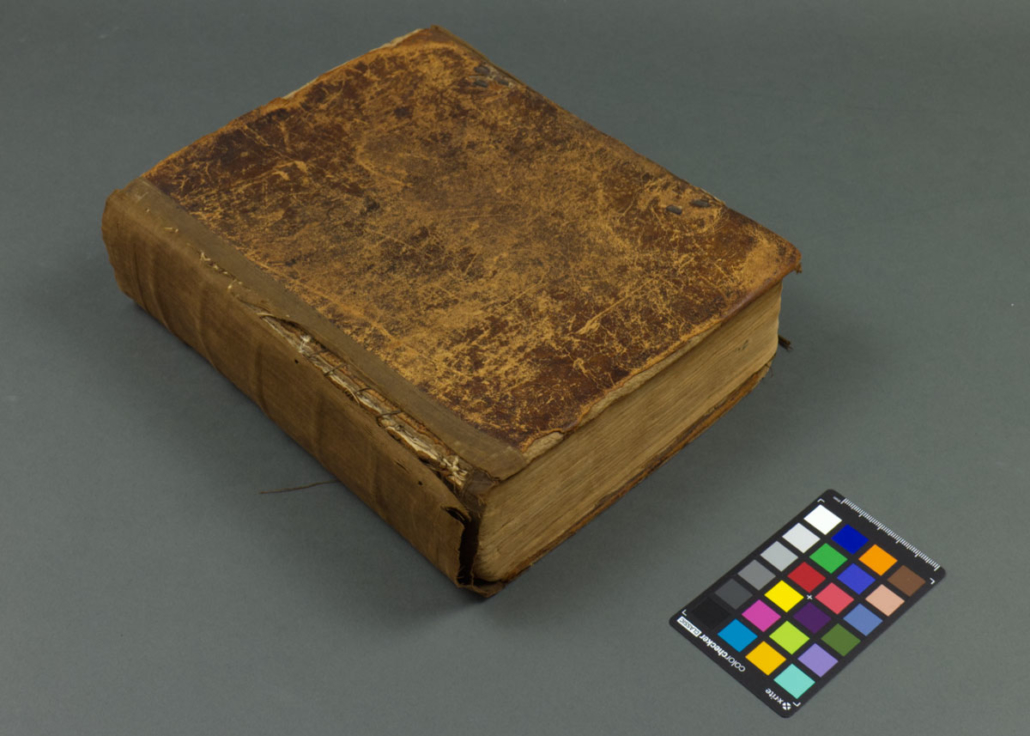

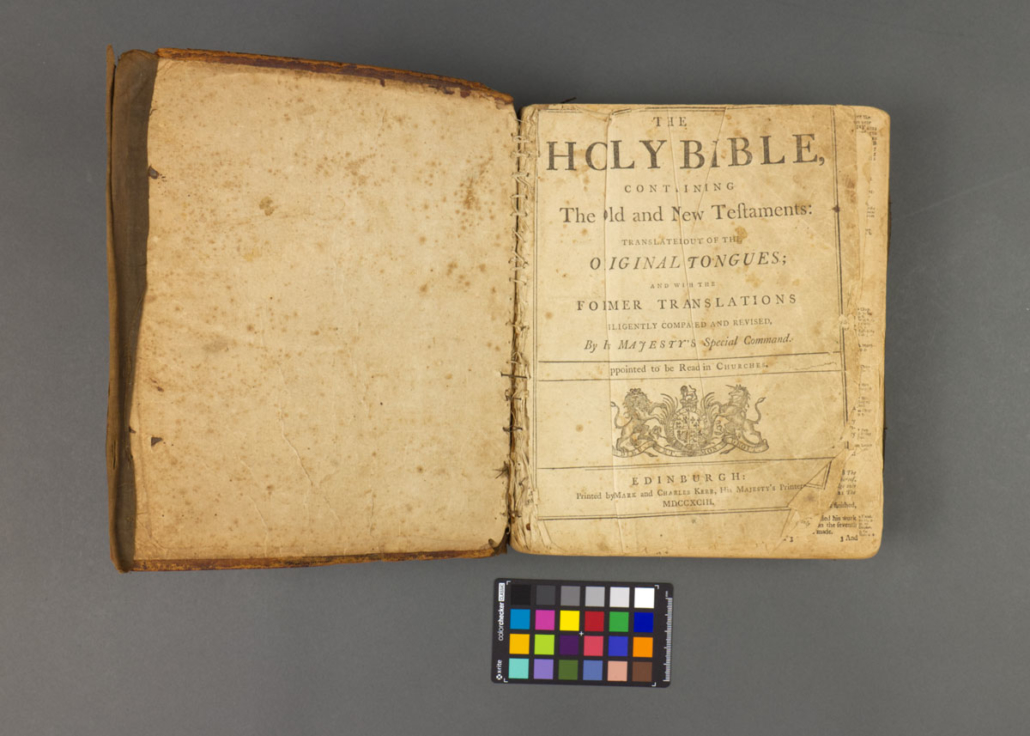

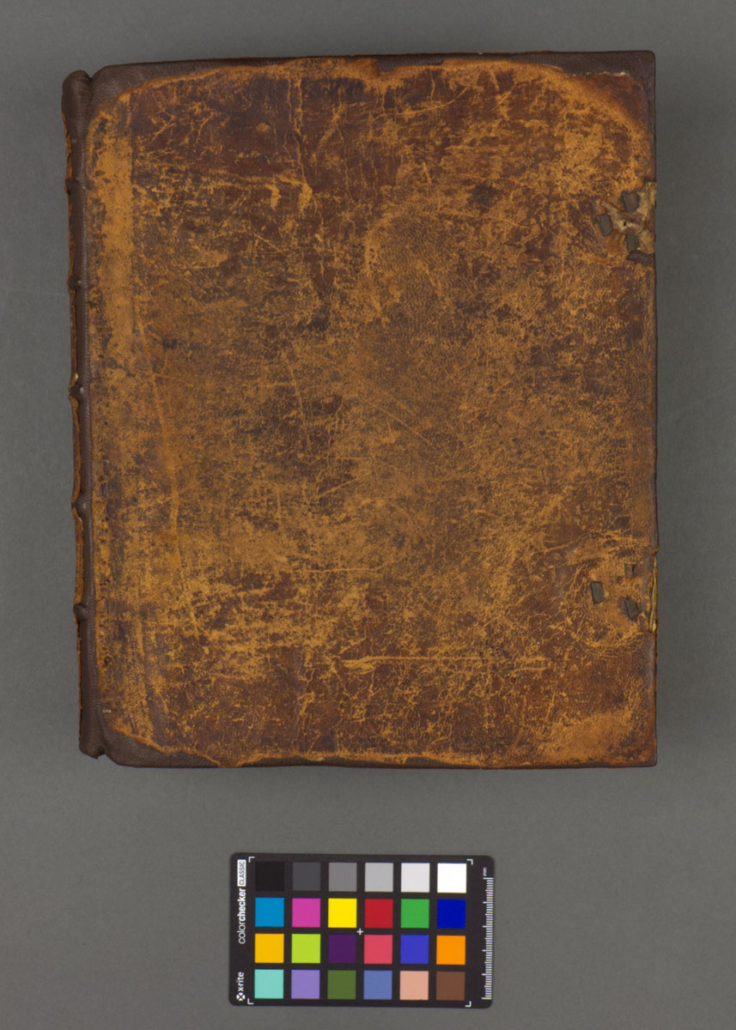

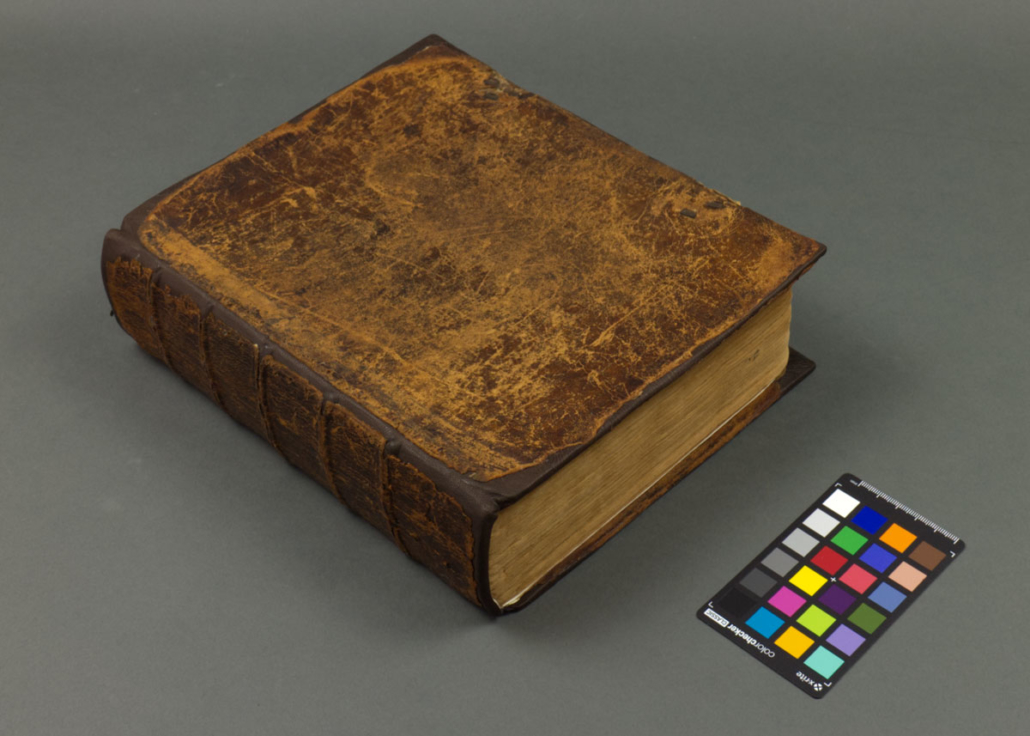

NS Conservation recently completed conservation work on Anderson Archival Founder Amy Anderson’s family Bible. The book dates back to 1793 and had been “heavily used and very well-loved” by direct descendants of the Pilgrims who traveled to America on the Mayflower. Conservation retains the history of an object, and this Bible is full of history.

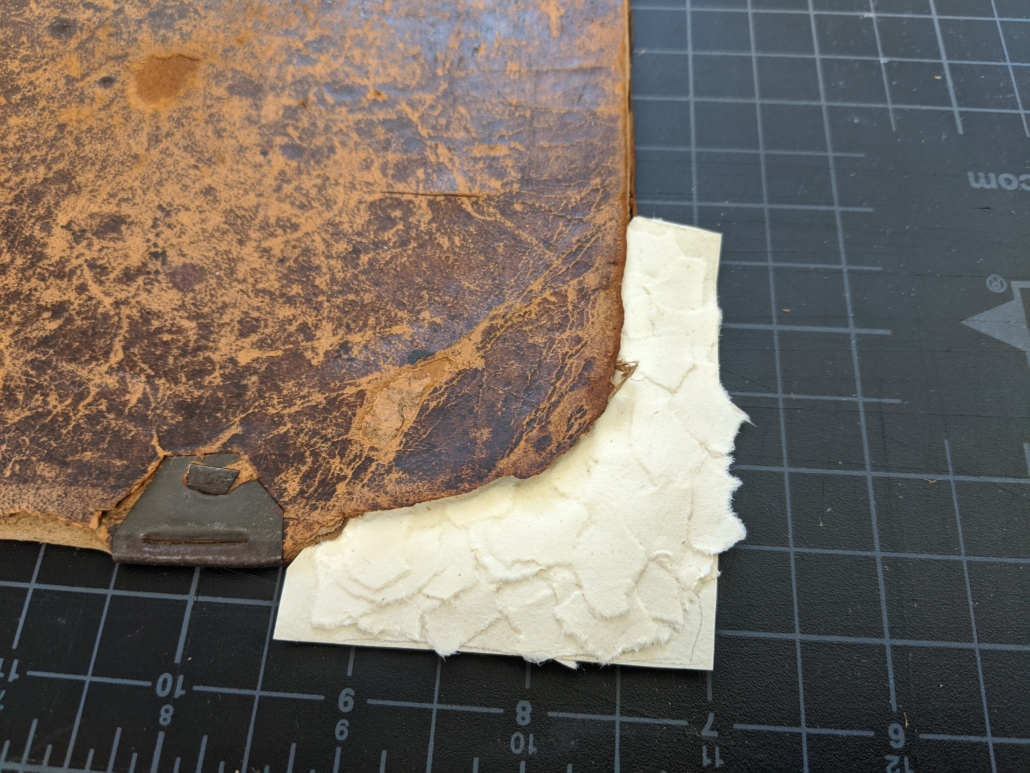

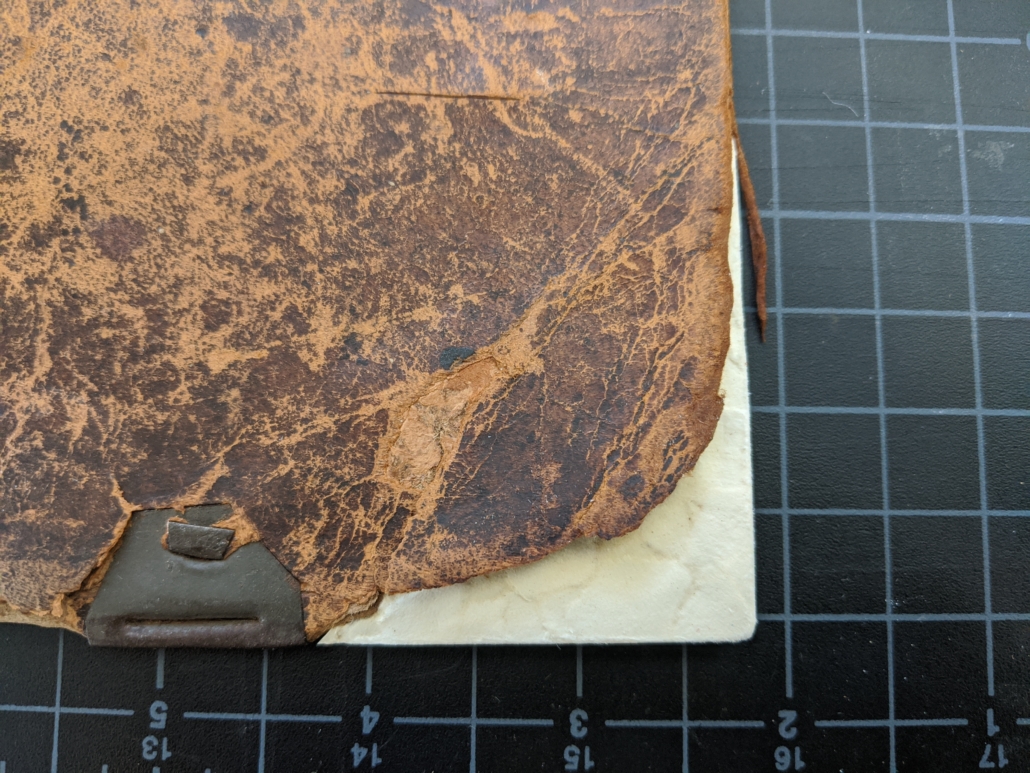

When Smutz describes the project, his voice changes subtly. Recalling the condition of the object, and the unique methods he used to return it to usable condition, seems to bring him great joy. “The leather along both joints where the boards attached to the rest of the book had broken and the boards had fallen off at some point. Someone had sewn them back on by literally sewing through the board and through the front and the back of the text to reattach them. The edges of the boards had lost leather… someone had covered the front with a brown cloth. It was a really well-loved book.”

“The key things in my treatment of this were to securely reattach the boards and to rebuild and recover the corners of the boards. They had worn away so far that the edges of the paper—the textblock—were exposed, and that can cause a lot of damage very quickly. I rebuilt the board corners, and reattached the boards. I used cotton cloth to reattach the boards to the spine of the book. I put new leather that is a similar color to the original leather over the top to cover up the repairs.”

The final result makes it clear that the book has lived a long, full life.

Why Conserve?

Clients like the Andersons come to NS Conservation with a variety of expectations for their historical objects. Individuals tend to want to enjoy the objects, and to be able to pass important books down to future generations in good condition. Collectors want to know that their investment will last. Collectors often seek customized storage to ensure the longevity of their collection. Museums and other institutions seek physical conservation in order to make a book usable by researchers or stabilized for display.

For individuals, collectors, or institutions seeking physical conservation of their objects, Smutz outlines what to look for in a conservator. The field began with master/apprentice arrangements, but in the 1980s shifted to master’s degree-holding. So, when looking for a conservator, a degree is great, but may not apply to everyone. “The only way to be a good conservator is to do conservation work,” Smutz explains, laughing. Other clues that a conservator is one who will deliver quality work are an AIC membership and a long history of work. Don’t be afraid to ask for examples.

A Partnership in Conservation

Smutz’s dedication to physical objects shows in the way he talks about their value. “For some researchers, for certain projects, having the physical volume in your hand can be very important. There’s something that can’t be captured digitally about the object,” Smutz explains. “Feeling the weight of the item in your hands, you can see where a past reader has dog-eared a page and flattened it back out. You can sense what the cost was to make this item by—is it handmade paper, is it machine-made paper, is it leather, is it cloth? Has it been used heavily; has it been used at all? Those are things you can really only tell by seeing the physical object.”

However, without digitization, true preservation of the material and its text remains incomplete. For objects that are very fragile, or where their importance for researchers lies in the text, a digital copy allows multiple people to access and do detailed research without inflicting additional damage on the original. Creating opportunities for access and research is what Anderson Technologies is all about.

Noah Smutz sums up this connection of the fields: “That’s why digitization and conservation are great preservation tools. Because they work together to both provide greater access as well as ensure that the originals survive into the future.”

Are you seeking the conservation of an object or collection? Noah Smutz can be found through his website, NS Conservation, and documents much of his process on his Instagram, @nsconservation. Anderson Archival can be reached any time at info@andersonarchival.com or by calling 314-259-1900. Physical conservation and digital preservation often go hand in hand. Consider what future you want for your historical objects, and reach out to us today.