Anderson Archival sat down with Marie Cayce, Digitization Specialist and Collections Assistant at the National World War I Museum & Memorial in Kansas City, MO, to discuss their amazing collection and how Anderson Archival was able to help digitize some of the most difficult items.

What has your career at the National World War I Museum & Memorial been?

MC: I interned with the National WWI Museum and Memorial in 2017, adding letter transcriptions that had been created by the Over There: Missouri & the Great War project into our Online Collections Database. After completing my undergraduate degree in History and part of an MLIS in Archival Studies, I returned to the Museum and Memorial as a Digitization Technician in 2022. In 2024, my title changed to Digitization Specialist and Collections Assistant to reflect my extra work with the collection, especially in regard to our Main Gallery upgrades.

What has your career at the National World War I Museum & Memorial been?

MC: Creating a photo studio out of an under-utilized closet space to improve the quality of our 3D object photography has been my favorite project to date. What started as a storage closet has become a space that suits diverse object imaging. A little bit of equipment went a long way and the pictures that we take now are both higher quality and quicker to take and process than what we had before.

The Museum and Anderson Archival have collaborated on two projects so far, Camp Newsletters and Posters. For materials that you have digitized in the past, how has the Museum handled them? Has there been any limitation or struggle in the past?

MC: Most of our collections are donated rather than purchased and are quite varied in the type of objects they contain. We prefer to process and digitize whole collections at a time rather than cherry picking out objects to scan. Objects are stored by their type rather than with their collection like you might expect at an archive, but arranging, describing, and digitizing one collection at a time ensures that we are able to glean as much contextual information as possible. For example, many uncaptioned photographs may be more easily understood after reading through papers related to that person’s military service.

For flat objects, the Museum and Memorial has Epson Xpression 12000XL scanners. Because we get many internal and external requests to use our images, we scan everything as 600 dpi TIF files. Because of upload limitations, we display compressed JPEG files in our Online Collections Database, but we retain the TIF files as our actual digital product. Anything that is too large for a single scan is scanned in pieces and stitched together in Photoshop. This is a time-consuming process and requires significant processing power to achieve, which is why we were thrilled to work with Anderson Archival on our larger objects. This is especially true for objects that are too large to even be scanned in pieces or those mounted to boards. In that case, we photograph them with a digital camera, but the end result is not as high quality as a scan can achieve. There were a number of beautiful, oversized French posters that I am especially pleased to have in the high quality that they deserve!

Let’s talk about the Camp Newsletters. Would you share some background on this collection, and why digitizing them was a priority?

MC: Camp newspapers are a special type of historical record, being collective but also personal. These range in size, breadth, and professionalism from single-page copies of a typewritten sheet to fully-fledged publications akin to city newspapers. Some soldiers used the papers as an outlet of expression, and many enlisted journalists simply continued the work they were already trained in.

Newspapers are a prime example of objects that were not designed to last. They were printed on thin paper that had aspirations of becoming confetti because they needed to be produced cheaply and quickly. The procedures for storing such fickle pages has been considered and reconsidered many times in the GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) world and many institutions in the era of Newspapers.com do not dedicate resources to their preservation. To the question of which is the important piece, the information or the object itself, newspapers typically apply to the former. However, we believe that camp newspapers are worth the time and effort to not only digitize, but also to keep.

Very few historical sources bridge the personal and collective spaces in a way that provides such insight into the experiences of these men and women over the course of the conflict. The papers were created in vastly different environments. Ships often published the news they had been cabled as well as inclusions by the sailors on board. Units continued to publish as they moved and some had a shifting format to adapt to these changes. With limited scope and printings, the number of surviving issues of some of these papers is quite low so getting them scanned is a preservation priority.

After the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, the American armed forces were reorganized as the Third Army (Army of Occupation) to oversee the demilitarization of Germany and this was the same for other Allied forces. Thousands stayed in Europe through 1919, but this period is often overlooked because it followed the ceasefire. Digitizing camp newspapers is one way to ensure that the work done during this time and those who did it are remembered.

These papers show a variety of content and differing levels of seriousness and production quality. Ships often produced a single, two-sided sheet daily as they received news from both sides of the ocean, whereas the Field Service Bulletin published weekly from their office, just a stone’s throw away from the Eiffel Tower.

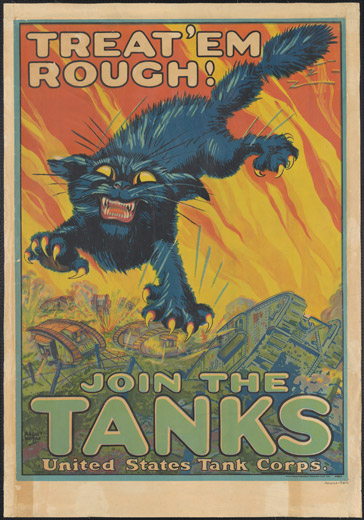

What about the Posters? Our team was especially moved by these! At one point, we pulled up a side-by-side comparison of the U.S. posters with Germany’s. Would you share some information about the posters, and again, why digitization was a priority?

MC: Posters are an exceptional medium within our collection. They are bold, bright, and colorful with striking text and powerful images expressly created to evoke strong feelings and prompt quick action to support the war effort. Many nations, themes, causes, organizations, and languages are represented by the Museum and Memorial’s poster collections and often touch on far-reaching repercussions of the war.

The Museum and Memorial’s very first collection, 1920.1, is a group of 600 posters that were collected by Kansas Citians to preserve the history of the war. The people’s same overwhelming passion and patriotism that funded and built the Liberty Memorial also started filling it with documents and objects for preservation and display. Not just a piece of remembrance of sacrifice, the posters were already piling up months before the ceasefire, kept in storage at the Kansas City Public Library. These posters are the heart of our collection and make up half of the posters that Anderson digitized for us in this project. In 2026, the Museum and Memorial will celebrate its Centennial, having been dedicated by President Calvin Coolidge on November 11, 1926. I believe that having that original collection scanned will remind Kansas City that we have not forgotten their contributions.

Posters are an automatic inclusion into nearly every exhibit because of their strong visual storytelling capabilities and striking presentation. They are also simply enjoyable to engage with on any level. Since we do not have a particularly large collection of art, posters add to the diversity of media that we display and add significant visual interest. Their size makes them more vulnerable than a letter or a photograph that can easily be moved, so it is ideal to have our posters searchable online to minimize the need for physical contact.

Here are three that have a good visual representation of the collection:

These posters reflect varying methods for capturing the audience’s attention through color, symbolism, and movement. At their core, each is trying to spur the viewer to action. Victory and peace are ripe for the taking, the images in these posters suggest. Each portrays some desired outcome that could be achieved with the labor or financial support of the nation but have taken different approaches as they target different groups. These images would have been displayed in shop windows, in public buildings of all sorts, even plastered to walls outdoors. Not only were they hoping to garner support, but they were also competing against many other agencies and organizations trying to garner the support of an already taxed and war-weary populace.

What has it been like to work with Anderson Archival?

MC: Working with Anderson has been smooth throughout even with a large, multi-phase project. The digitization of these materials is only one piece of a much larger in-house effort to reorganize and rehouse our poster and map collections, which have been arranged by the catalog numbers they were assigned during the era of the card catalog. Anderson’s experience was evident as they guided us through the process and worked out solutions for all the little quirks that each project presented.

How does the Museum plan to use the digital images of these collections?

MC: Our priority for digitization is to get more of our collection onto our online database in a format that is high quality and useful for users. Now that we have the images, we’ll be moving forward with creating a record for each object. These objects receive item-level descriptions to make them as findable as possible, so the process is time-consuming. This poster, “Trench Warfare” by Lucien Hector Jonas is a great example of the finished product that we will create for all the objects that Anderson has scanned for us.

Is there another collection at the Museum that you hope will be digitized?

Absolutely! In addition to our maps, we’d really like to have our photograph albums digitized. They are not large-scale, but they are competing against everything else to get digitized. The photographs contained in them are typically small and each album can contain several hundred, so the work of isolating each image for albums that we consider to be significant enough to warrant item-level description is a lengthy project but well worth the effort.