Archivists are often eager to illustrate the one-of-a-kind perspective their collection presents. Artifacts like postcards, candid photos, and personal correspondence offer a way to tell previously untold stories about our origins.

However, historical archives not only provide a peek into the past, but they also offer new context around the histories we think we know. The Dow family, best known for starting Dow Chemical Company in 1897, has one of these legacies in the United States’ history. We talked with Historian Samantha Engel about the digitization project Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation undertook with Anderson Archival to digitally preserve materials from two different Dow family collections.

Sam was a historian at the Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation for seven years, having since moved to a position directing a literacy nonprofit. Though she’s no longer with the foundation, she had a lot to share about her time with the collections, the preservation project with Anderson Archival, and the impact of digitization.

AA: Can you describe your role and relationship to the collections?

I am the historian here for The Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation, and within that is Dow Gardens. When it comes to the archives specifically, I oversee everything that happens with them: creating workflows for transcription and cataloging, receiving research requests, using the archives to inform the work being done within Dow Gardens as well as programs and things that we do. And then, of course, overseeing the overall preservation—within that, digitization—of the collections.

Our collections here all relate to the Dow families, specifically Herbert, who was the founder of the Dow Chemical Company, and his wife Grace, and then their children. The Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation was set up by Grace Dow in 1936, after Herbert’s death. She created the foundation to be a charitable organization, so we are still a family foundation that gives grants to nonprofits throughout the state of Michigan, for a variety of focus areas that were important to Grace.

“The less we have to handle the documents, the better. If we just pull up the digital copy and look at it that way, it’s far kinder to the paper.” – Samantha Engel

AA: What kinds of materials do the collections contain, and how are they used?

When Grace Dow passed away in 1953, she left all her property—her house, real estate, property, and belongings—to the foundation. Her children were all the trustees of the foundation at the time. Tucked away within her house, The Pines, which is still part of the Dow Gardens campus today, were letters, tax returns, photographs, and all kinds of things. Nobody really did much with it for many decades. The house became a national historic landmark in 1976, so they began gathering the papers and artifacts within the home and dividing them into collections. Today, that is what forms our both artifact and archival collections.

There’s a lot of stuff I’m personally not so interested in, like much of the data related to the chemical company’s history. But we have tons of letters that the children wrote to Grace while they were in college. Herbert was also very interested in horticulture, so we have lots of photographs of what is now Dow Gardens. The photographs show us what life was like when the family lived here and the improvements [Herbert] was making. He was also very interested in his orchard, so one collection that we’ve already digitized contains correspondence with fruit growers and horticulturists throughout the country. They discuss new developments in apple cultivation, apple breeding… It’s fascinating—I had no idea there were so many different varieties of apples!

A significant use comes from sharing the story of Herbert and Grace Dow and their family with visitors to Dow Gardens. We’re always exploring new and engaging ways to do this so visitors understand why the Gardens is here and not the playground of the Dow Chemical Company, a misconception some people have. We have nothing to do with the Dow Chemical Company today. We don’t receive many research requests, perhaps a couple a year. Mostly, we use the collection internally for program creation depending on which collection we’re looking at. For example, the kids’ college letters are frequently used in our programs and tours because they provide a glimpse into who these people were.

I would love to have the collections be used by more researchers in the future. But before we’re welcoming tons of researchers, I really want to get the digitization and cataloging in order. The less we have to handle the documents, the better. If we just pull up the digital copy and look at it that way, it’s far kinder to the paper.

“From the beginning, I felt that there was a level of care that I have not experienced previously.” – Samantha Engel

AA: What was The Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation’s previous experience with digitizing these collections?

[Before the project with Anderson Archival] we had digitized about an eighth [of all the materials], and that’s just me looking around at my shelves and thinking about how much space it takes up. It could even be less than that, to be honest. The Foundation worked out an agreement with a local university [for digitization], and I joined not long after that process began. We continued working with them, but then COVID happened, and they eventually stopped doing digitization work for outside clients, now solely focused on their own extensive museum and archive.

AA: What can you tell us about the two collections Anderson Archival digitized?

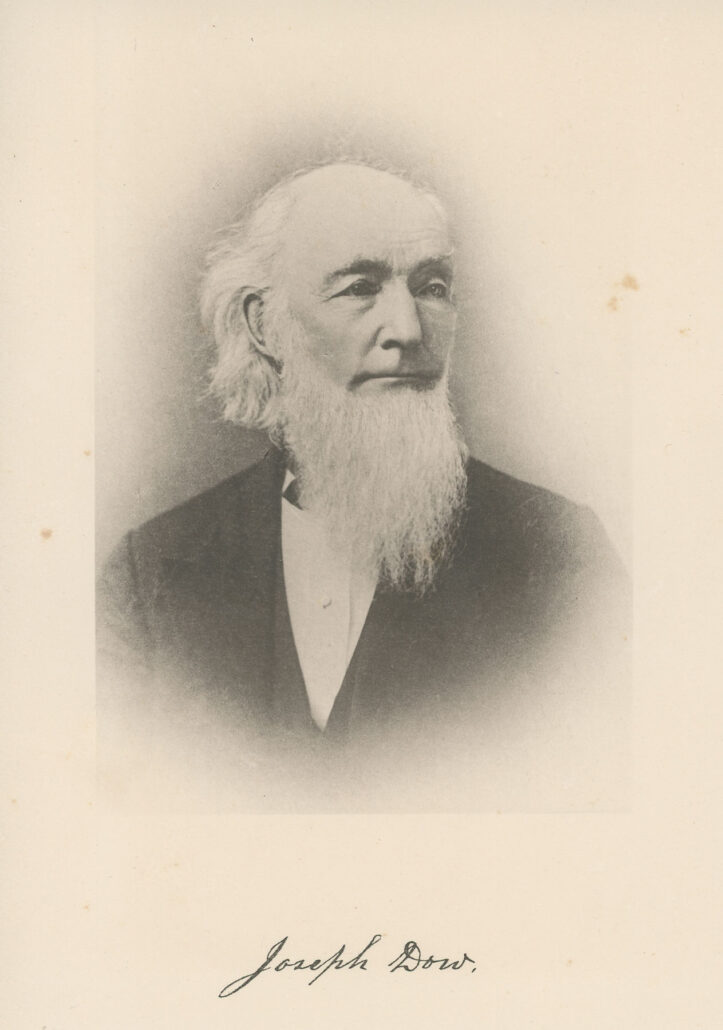

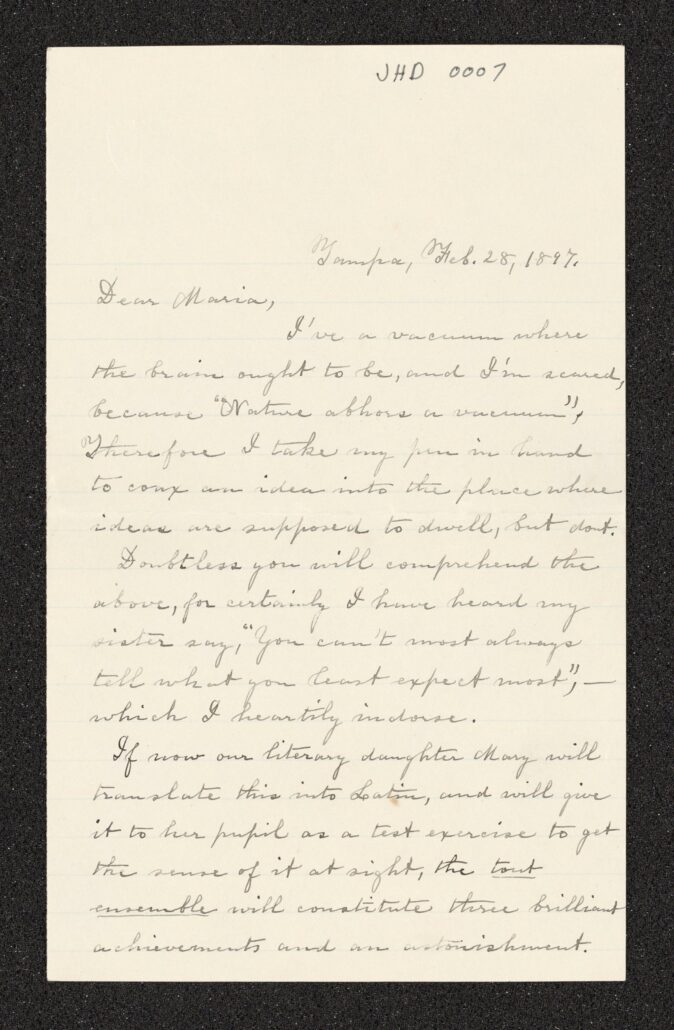

[This project focused on] the Willard and Joseph collections. Joseph Dow was Herbert Dow’s father, and many of his letters are addressed to Herbert. They shared a similar inventive, tinkering mindset, and even jointly held a patent. Herbert has somewhere around 90 patents to his name, and Joseph contributed to at least one of them that I know off the top of my head.

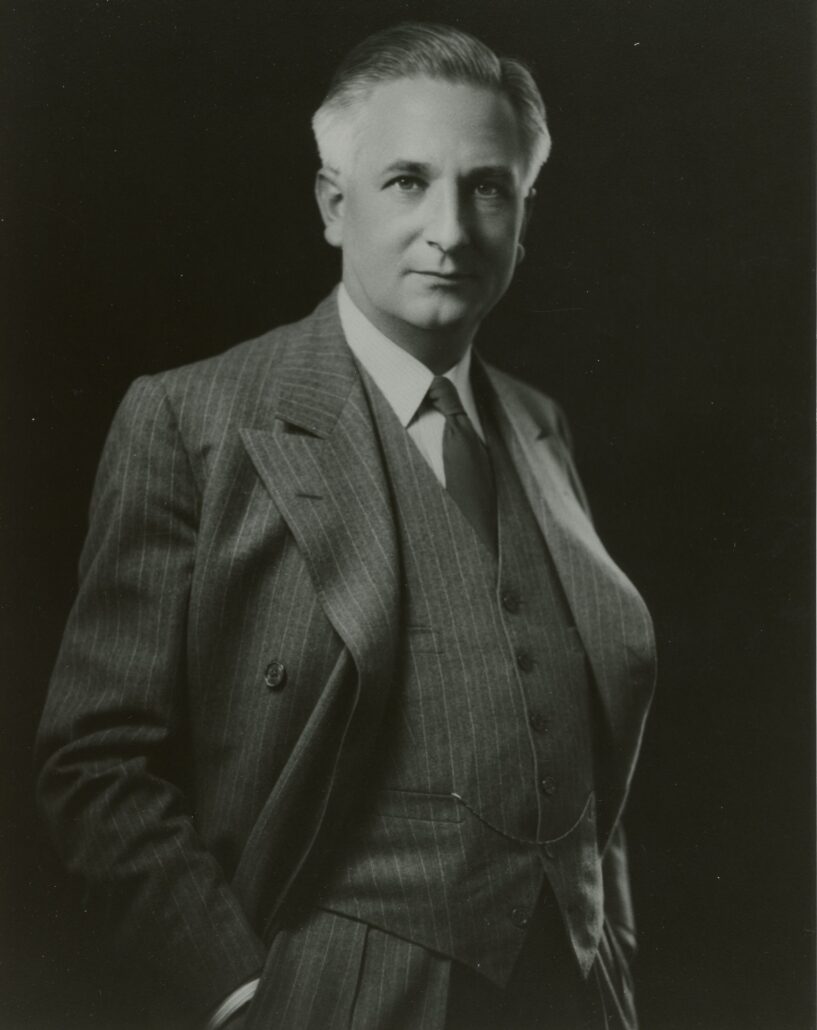

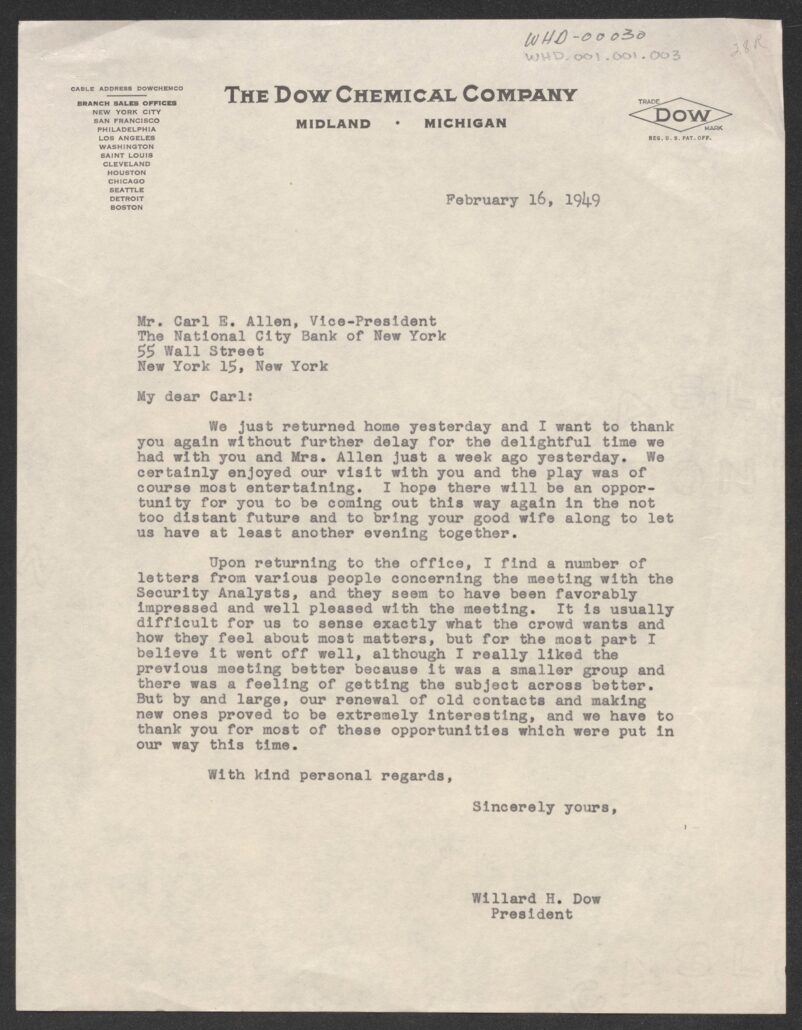

Willard, on the other hand, was Herbert and Grace Dow’s oldest son and third oldest child, who took over as president of the Dow Chemical Company after Herbert’s death in 1930. This collection contains a lot of correspondence, speeches, and business dealings from his time leading the company. His personal letters and family correspondence, including those written while he was in college, are part of another collection we have. He was good to his mom and his sisters, especially during their college years together. Willard holds a special place in my heart.

I can’t wait to dive into the Joseph letters in particular. I already know I love Willard, but I really want to learn more about Joseph. I don’t know much about his personality or the nuances you can pick up from someone’s writing and what they write about. That’s one thing I’m looking forward to having a chance to look at more.

AA: What factors contributed to choosing your new digitization partner?

I wanted to make sure I found the right [partner] for the job, because I’ve had experiences where the [firm] wasn’t as helpful throughout the process and didn’t show the same level of care [as us]. These aren’t documents you can feed through a scanner. It’s never good when you get a file back and you realize you need to correct it all. The numbering system was the biggest thing. That is based on a numbering system for the archive that was already in place before the collection was ever digitized [and had to be matched by a new vendor].

From the beginning, I felt that there was a level of care that I have not experienced previously. Anytime there needed to be a readjustment or a question came up, it was brought to my attention so that I could answer it, and we could move along. I was very happy with how everything worked.

AA: Do you have advice for other archivists or historians who are protective of their collections and might be hesitant to send them away for digital preservation?

It was a very odd feeling, sending my things away. When I packed it all up and saw it drive away, I was like, “All right, I hope I see you again!” Anything can happen when you’re traveling hundreds of miles on the freeway. Through no fault of anybody’s, an accident can happen, and suddenly my papers [would be] billowing all over the place. They’re irreplaceable things.

At one point on our end, a question of insurance was raised, and I said, “It’s paper, so there’s not some kind of market value. It’s valuable to us because we care about it, and we can never replace it. Insurance isn’t really something that I’m thinking about because if it’s gone, it’s gone.” It’s a funny thing, because you feel so much more secure about the safety of the collection once it’s digitized. It’s a lot easier to keep eyes on the collection when it’s not just papers in a box.

When I worked at a museum in Flint, Michigan, we experienced a fire, which raised a lot of questions. How much should we invest in restoring an item when what we get back isn’t the original? At what point do we decide something is no longer salvageable? Insurance was another issue; the payout could never truly compensate for the loss. Sure, we could replace a desk, but it wouldn’t be Mr. Bailey’s desk anymore. It might be a period-appropriate desk, but the essence of the original would be lost forever. You come at things a little bit differently, I think, after that.

Thanks to Samantha Engel and The Herbert H. and Grace A. Dow Foundation for this interview and a successful project!

Do you have delicate or unique historical document collections that need to be preserved against deterioration? Give Anderson Archival a call to learn how we treat your collections like our own and protect them through digitization.