How do we balance our responsibility to accurately record history and our dedication to preserving it ethically?

Experienced archivists know how to separate their personal feelings from the materials they set out to preserve. They aren’t always tasked with endorsing the material, but simply preserving it. Dedicated archivists feel obligated to document the past, regardless of their opinions about the material.

The Society for American Archivists (SAA) first established an official code of ethics in 1980. It emphasizes both the need to make collections accessible to its audience and limits that audience in ways that protect “the donors, individuals, groups, and institutions whose public and private lives and activities are recorded in their holdings.”

In order to examine the role of ethics in digital preservation, consider an interesting case study from SAA’s research.

Controversial Correspondence

President Warren G. Harding first served in the US senate from 1915-1921, and then in the Oval Office from 1921-1923. Before his time in politics, he owned and operated a local daily newspaper, The Marion Star, with his wife Florence. He eventually became an active and well-known Republican due to his influence in local media, and his air of refinement and confidence led to his rise to national leadership.

The illusion of success didn’t last long into his presidency, however. Harding built his political platform on restructuring the government after the havoc of WWI, and this national inertia left a door open for corporations to corrupt the government from the inside out. Under-the-table deals like the Teapot Dome Scandal happened behind Harding’s back. His term as president was cut short when he passed away in 1923 before he could witness the extent of his cabinet’s infractions.

Our twenty-ninth president was also quite the Lothario, as White House rumors suggest. Only some of the transgressions during Harding’s short presidential term have been proven, but an affair before his time as president serves as the cherry on top of a less-than-stellar reputation. Before his days in the US senate, Harding befriended an acquaintance of Florence’s named Mrs. Carrie Fulton Phillips, and they began an affair that would last the better part of fifteen years. A closer analysis of Harding’s letters to Phillips reveals the explicit nature of their relationship, as well as hints that Phillips may have been a German spy, though those rumors are yet unfounded.

Clandestine Preservation

Nearly forty years later, an archivist named Ken Duckett became the curator of manuscripts for the Ohio Historical Society (OHS) from 1959 to 1965. The Harding family was fiercely opposed to any facts coming to light that might affect the former president’s reputation, which complicated negotiations with the Harding Memorial Association’s (HMA) materials. The HMA was carefully filtering the materials and removing anything that painted Harding in a negative light.

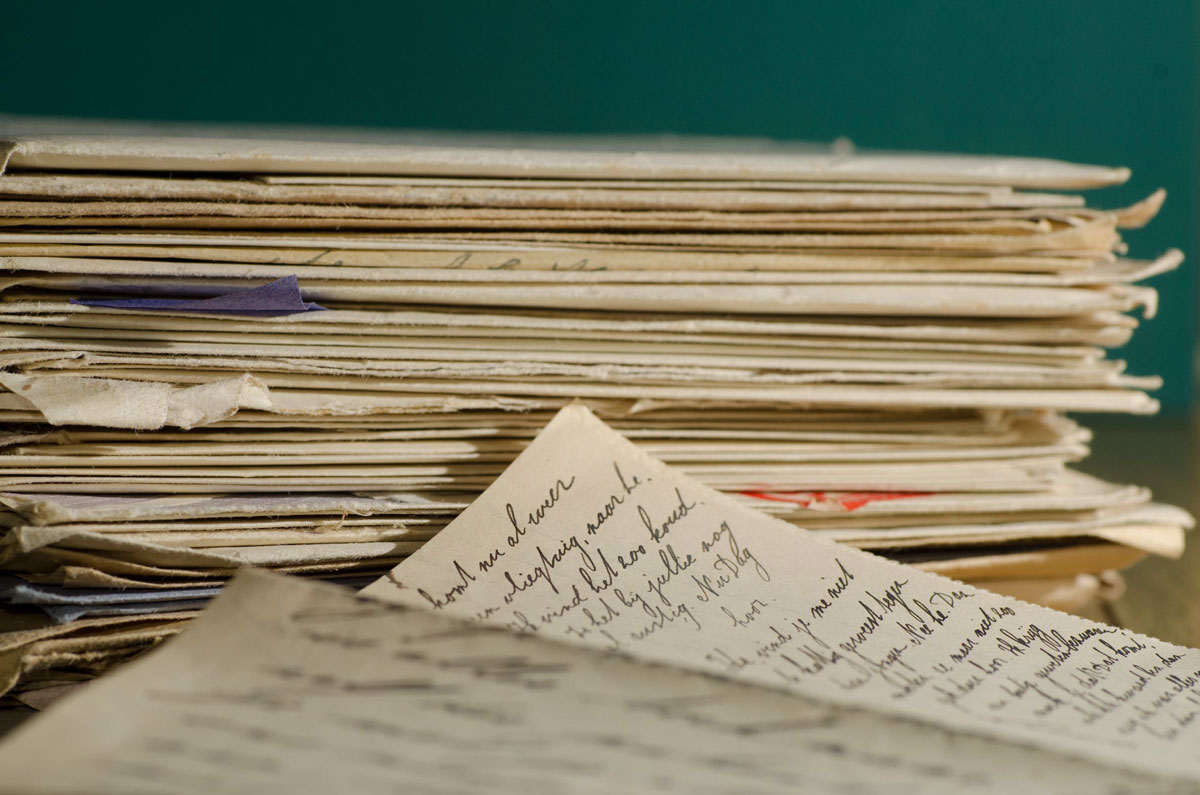

After Phillips’ death in 1960, Duckett managed to procure a collection of 240 letters and other correspondence between Harding and Phillips. When the box full of letters came into his possession, Duckett protected them in a safe deposit box until the Harding family agreed to hand over their historical materials. But still he worried about their safety and the validity of the historical record. For this reason, he made the controversial decision to secretly create microfilm copies of the letters and hide the originals in an OHS vault. Had the HMA known about these letters and their subsequent copies they would have immediately been destroyed, even though the love-letter-less collection they eventually presented to the OHS left significant gaps in Harding’s political legacy.

“On July 22, 1964, he wrote to Oliver Jensen of American Heritage ‘I have heard the words “burn, destroy and suppress” so many times since I acquired the papers, that I am determined that extraordinary precautions must be taken to insure their preservation and use by historians.’ Included with the letter was a copy of the microfilm sent for safekeeping. By taking this action Duckett was fully aware that he was placing his job at risk.”

After the release of a revealing Harding biography, a law suit from Harding’s family, and the resulting media circus surrounding the letter scandal, Duckett was forced to surrender all four known copies of the microfilmed letters—but secretly kept one copy for himself. This guaranteed that Harding’s marks on American history could never be erased, even if those marks were less than dignified.

The Harding family then donated the letters to the Library of Congress in 1972 after being assured they would be kept private until fifty years from the date the case was officially closed. The Library of Congress opened the letters to the public in 2014, mere days after Duckett’s death at age 90.

What Moderates the Test of Time?

Duckett’s choices raise some important questions about the ethics of documenting history. How does one determine what should be preserved? In a perfect world, all material with cultural significance would be around forever for future generations to learn from and enjoy. The act of preserving any material implies that it has inherent value—otherwise, why bother preserving it at all? But should sensitivity or, in this case, public image, override value?

At Anderson Archival, we respect the preferences of our clientele, and within those preferences we maintain utmost accuracy, confidentiality, and precision in preservation. Importantly, the SAA doesn’t draw clear lines to define accessibility and restriction for every collection because every collection is different. The job of each archivist is to preserve with these ideas in mind, and the preservation of the Harding letters serves as an exercise in ‘what would you do.’

Whether Duckett is a hero or an outlaw is up to each reader to determine. Striking a balance between accessibility and restriction is what Anderson Archival strives to do with every collection we work on. In fact, the majority of our projects thus far have been private, and kept confidential. At what lengths should archivists go to preserve history? We leave that decision up to you.

Do you have a collection that needs to be digitized, even if it’s only for your eyes? Need help determining the scope of its audience? Contact Anderson Archival today for a free consultation, or call us now at 314.259.1900.