How do organizations decide to digitize regularly used collections?

Infrastructural organizations like libraries, hospitals, schools, churches, and nonprofits rely on accurate, accessible records. Putting collections of essential records to the side for processing isn’t always feasible, and digitization isn’t fast when done correctly. Once an organization moves forward with digitizing their collection, decision makers often have to jump through hoops every step of the way to get the necessary funding approved.

To better understand the needs of nonprofits and other organizations that use their collections every single day, we spoke with recent Anderson Archival client Bernie Lockard. Lockard is on the board of Oakland Cemetery, which came to our firm with a collection of books dating back to the cemetery’s founding.

A Reverence for Records

The 34 wooded acres of Oakland Cemetery opened in 1864 in Indiana, Pennsylvania. “It’s been around for quite a few years,” Lockard says, “run by a nonprofit board and volunteers.” At the time the region needed more space to bury and honor their fallen Civil War heroes, and today the cemetery is the final resting place for around 20,000 souls.

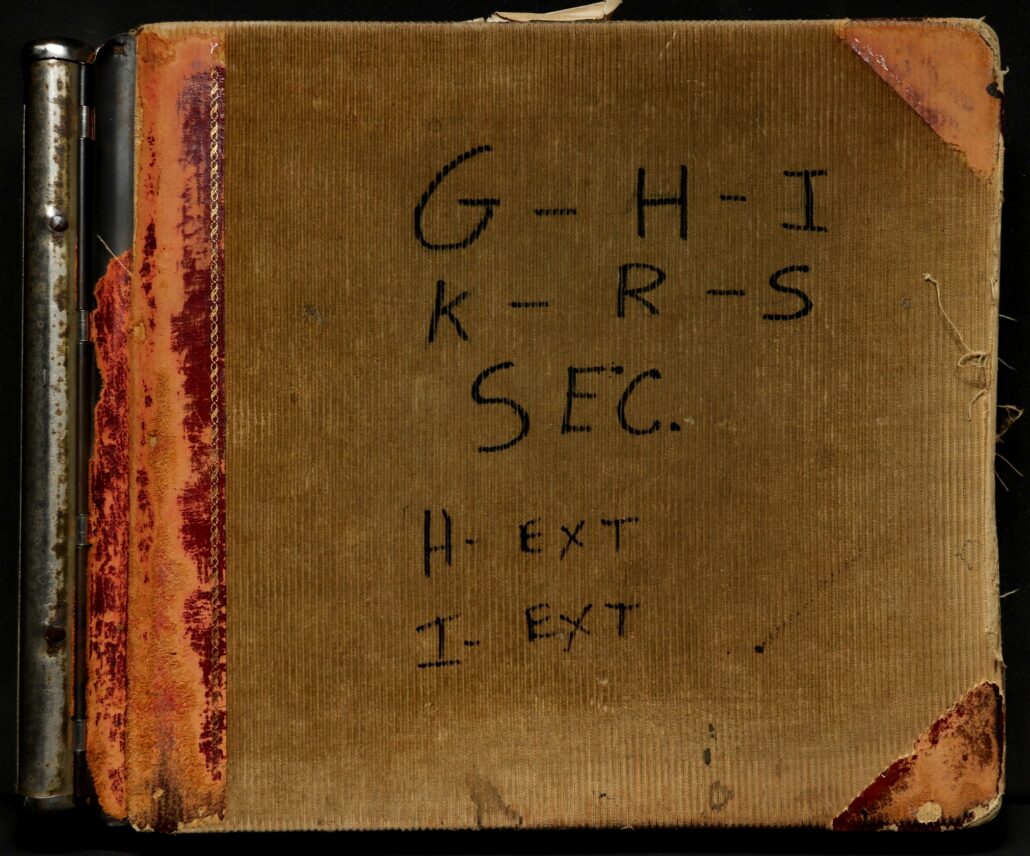

An astonishing amount of record-keeping takes place in cemeteries. “The last thing you want to do is go to bury a body and there’s someone else there,” Lockard says. Oakland Cemetery’s collection consisted of deed books, board meeting minutes, and cemetery lot records that stretched back to the 1800s. “We would access them if there was a question on deed ownership or the exact location of an interred body,” Lockard explains. “Some of these [plots] are in old sections [of the cemetery]. You might happen to sell an unsold lot in an old section, so you’d have to open the book to record on paper that happened.”

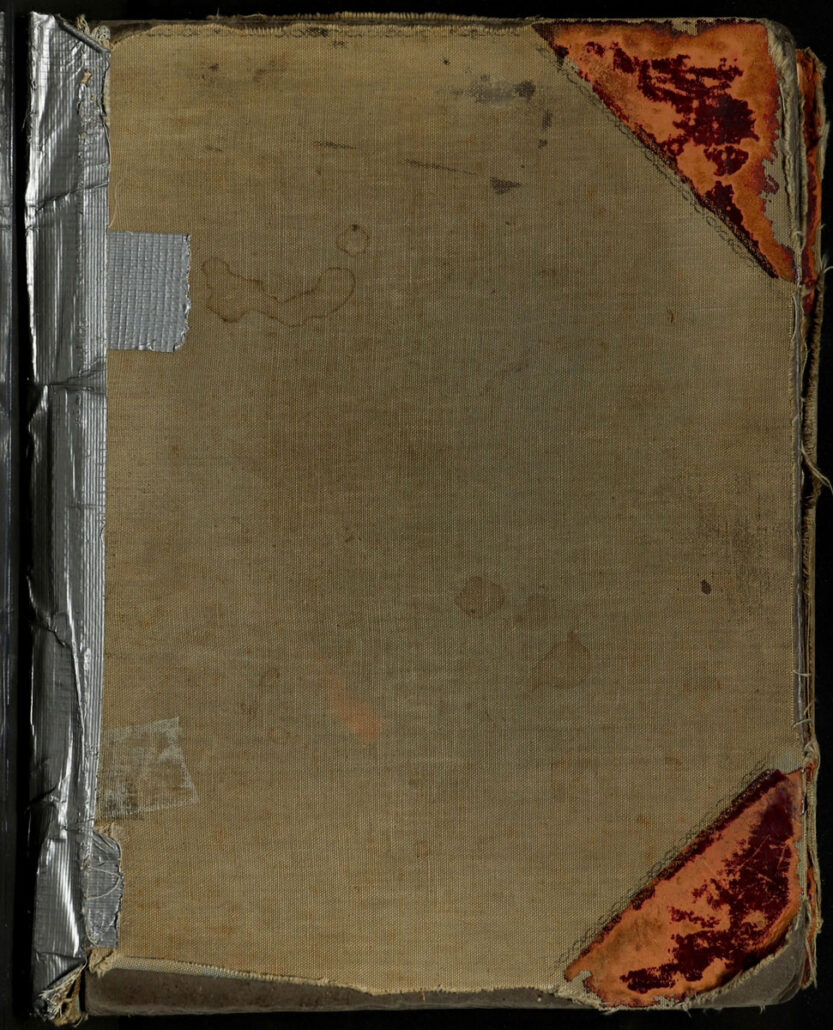

As one can imagine, materials of that age don’t hold up very well to regular use.

We knew that we couldn’t access them physically much longer… Every time you opened that book, you lost a piece of history.”

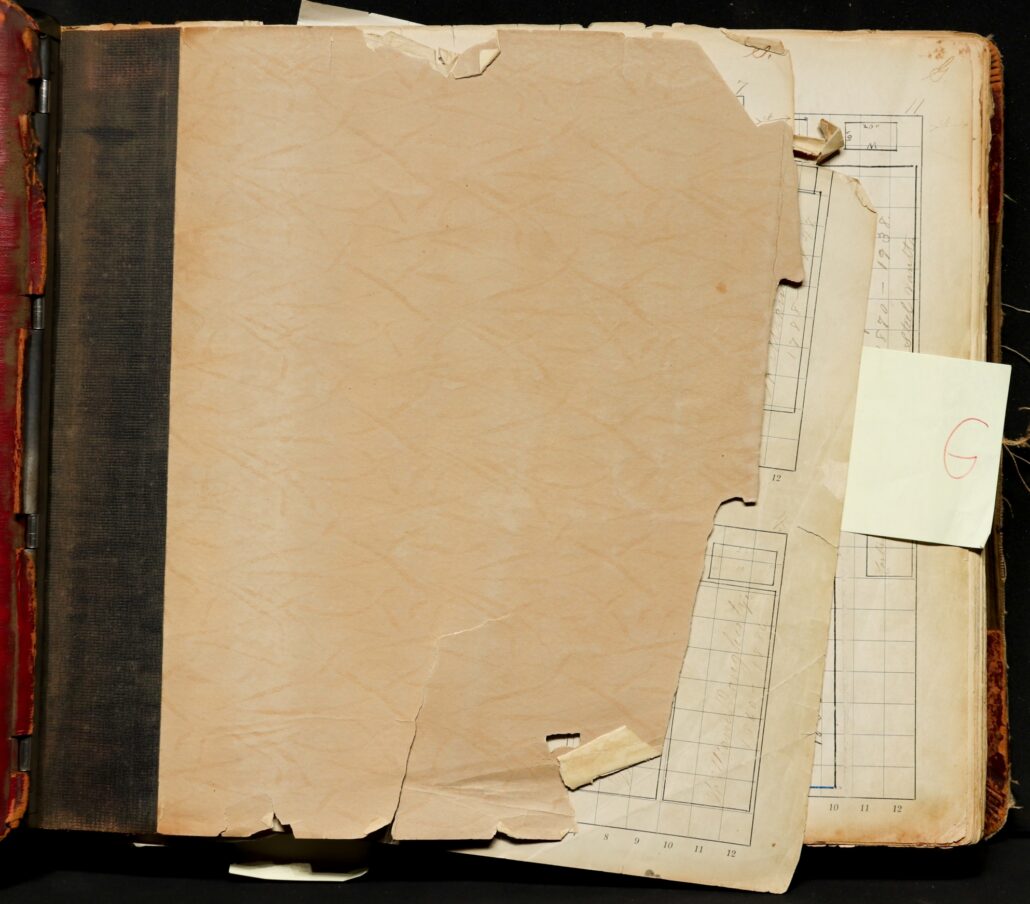

“They’ve previously just been stored in a safe and accessed when necessary, particularly the oldest one that was starting to fall apart,” Lockard says. The pages of this oldest and largest record book—an armful measuring nearly 24”x18”—were brittle and flaking at the page edges, leaving an outline of paper shreds behind if the user wasn’t careful.

Digitization was the logical preservation solution for these essential records, but getting this collection to our scanners would not be an easy feat. Lockard first had to present the project to the rest of the board of directors. “From a nonprofit board,” Lockard describes, “when we’re investing money into assets that will create revenue for us, it’s one thing. When we’re investing money into projects like this that aren’t going to produce revenue, it’s something we have to be more careful with. We’re not worried about cutting grass next week, [but] it’s important for us to remain proactive.”

What was it like to convince the rest of the board that digitization was crucial? “Well, it took two meetings,” Lockard says. “[In] the first meeting, we had some objections as to did we really need to do it? It wasn’t so much the money, it was the need to have it done. Again, that speaks to having to be careful with money spent on non-revenue projects like this.”

The second meeting about the project was more effective. “We actually showed some of the board members the books so they could understand the shape they were in. Then they pretty much agreed that part of our stewardship is to maintain these records.”

Investments Uninterred

That stewardship was the final piece needed to convince the board of directors. In fact, Oakland Cemetery had encountered digital preservation in the past for this reason. “We had undertaken a project about five years ago to digitize all our records. We have a database now that we have access to these books for that purpose,” Lockard says. “This is kind of the final step of this modernization project. Our goal now is taking these books to store inside one of the crypts, hopefully never to be accessed.”

As it turns out, the inconvenience of sending important and frequently used records away and budgeting for their digitization is a part of the stewardship that Oakland Cemetery’s board is used to. Cemeteries require endless expenses and investments that industry outsiders might never consider. “Trees and vegetation around the cemetery cost constantly as they need to be replaced,” Lockard says. “Trees are expensive, but we feel like it’s part of our part of our image.”

Investing in digital preservation is a part of Oakland Cemetery’s dedication to its patrons, both alive and interred. Lockard explains this best using the example of Chief State Supreme Court Justice John P. Elkin, an Indiana native who died in 1916. “His wife got this grand mausoleum for him and her family,” Lockard says. “In the early 1960s, the family gave the mausoleum to the cemetery.” As the structure aged, it started to rack up a list of expenses: a new roof, new pointing, patched leaks, and ventilation issues. “We spent $150,000 to fix it up. And it’s another one of these things that’s not income-producing but is part of the image.” Cultivating the cemetery’s environment as a whole includes preserving that history through paper records as well.

Oakland Cemetery’s new additions to its digital records database is currently serving the community in more ways than trees and plots. “Now that we have this [digital collection] we are sharing those files with a local historical society,” Lockard says. “At some point, access to this is going to make its way into our website as well. We are creating a historical tour of the cemetery that will probably link to the digital files, so you see the actual deed transfer that occurred or how someone passed.” The collection of massive record books and meeting minutes may have found their final resting place, but the digital versions live on to enhance the experience of the cemetery’s day-to-day operations—and hopefully patrons in the near future.

“We still have some books to get done yet,” Lockard shares. “The board didn’t approve all the money yet, but hopefully, that’ll happen in the next month or so. You know, when you have a cemetery with a board of old men, things take time to happen.”

Are you having trouble deciding how to preserve the collections your organization use every day? Give Anderson Archival a call to get the expert advice you deserve.