These days, some might consider letter writing an outdated form of communication or even a lost art. But at a time when one couldn’t simply send a text or email to a faraway love, these collections are a testament to everlasting human relationships. Correspondence has the ability to tell a story, and a collection of letters can keep a romance alive even after death.

We spoke with Carla Pasetti, whose family recently brought her collection to Anderson Archival for digitization help. The collection included hundreds of handwritten items from her father Armando to her mother Evelina, written in Italian. While this collection of letters and other paper miscellanea like postcards and translucent notes was in fairly good condition and enjoyable for the team to work on, it presented some other preservation challenges. We discuss working with a conservator to help organize and stabilize a collection before digital preservation occurs as well as the future of this romantic digitized collection.

AA: To start, what would you like to tell our audience about your collection and its history?

This was a collection of letters that my parents wrote to each other back in the early 50s. My father came to the United States back in 1938. He was fourteen years old and came from a small agricultural town of San Martino dall’Argine near Mantova, Italy. He came over to work for his uncle and aunt on The Hill [in St. Louis, MO].

On one of his trips back to Italy—which weren’t very frequent at that time, you know—he met my mother [whose] sister was engaged to be married to his brother. That’s how they met. I guess they immediately connected. When [my father went] back to St. Louis, they corresponded over about two and a half years before he went back to Italy and married her. And then a few months later, she came to join him in St. Louis.

There were quite a few letters and postcards, [which] I think totaled 473. We always knew that they were around, you know, just in a cigar box in the basement. My mother passed in 2019, and my father passed in late 2020. We wanted to just leave [the collection] until he had passed, but we always had an intention to do something with it.

Did you anticipate any particular challenges to digitizing these letters?

I knew that, in the end, I wanted to make a master book of the letters, and I knew that I wanted to use something like Shutterfly or Snapfish. I wanted this to be an homage to their correspondence back and forth. I was like, ‘I’m not going to alter these or edit at all. I just really want to have a picture of each letter that is clear enough that I can read.’

Now, some elements of the collection weren’t letters. Can you speak to some of these other items, like the postcards and translucent materials?

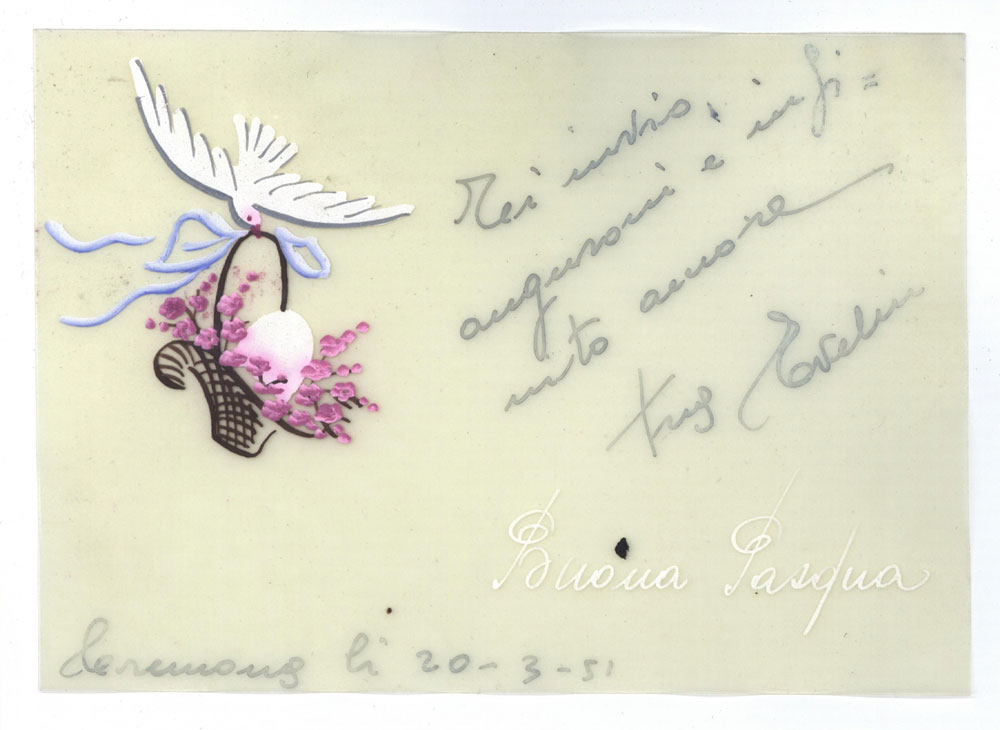

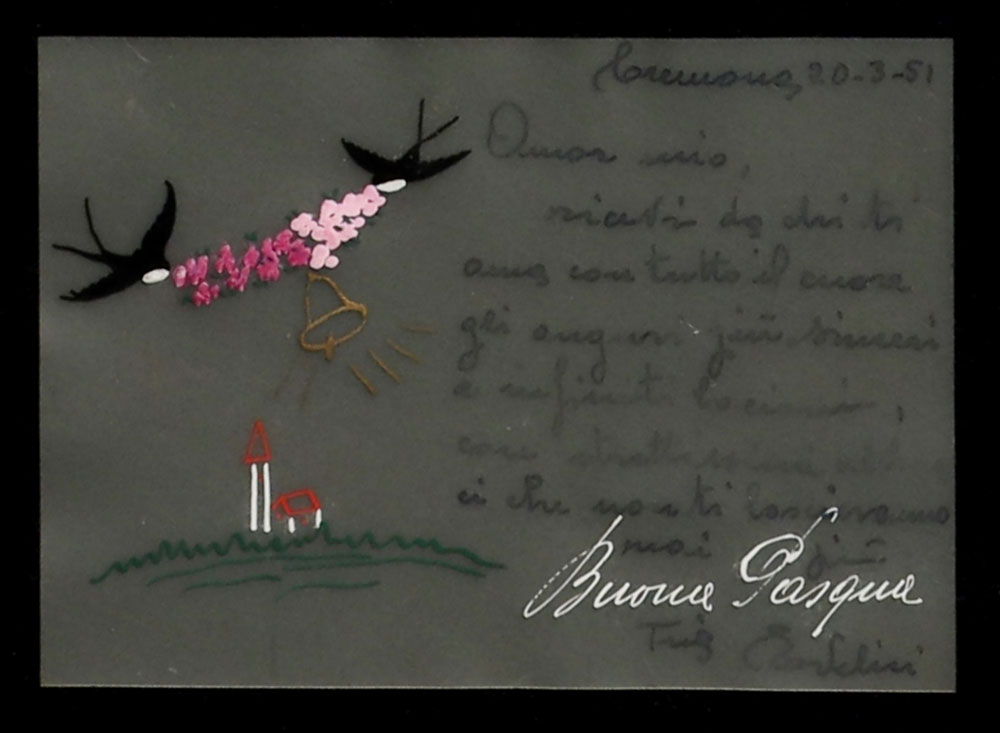

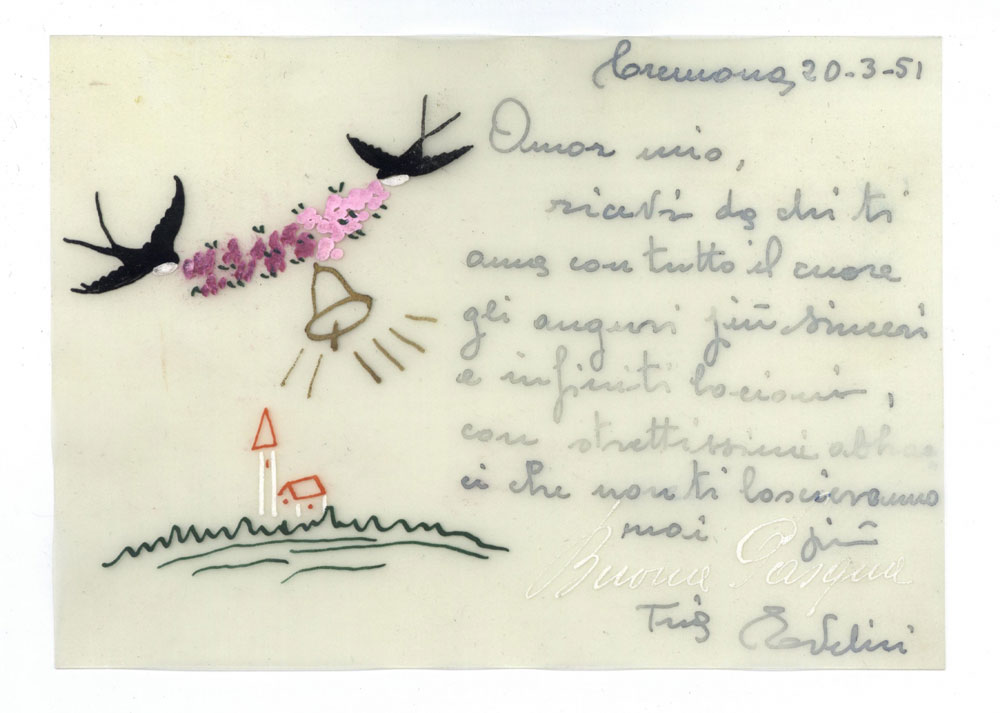

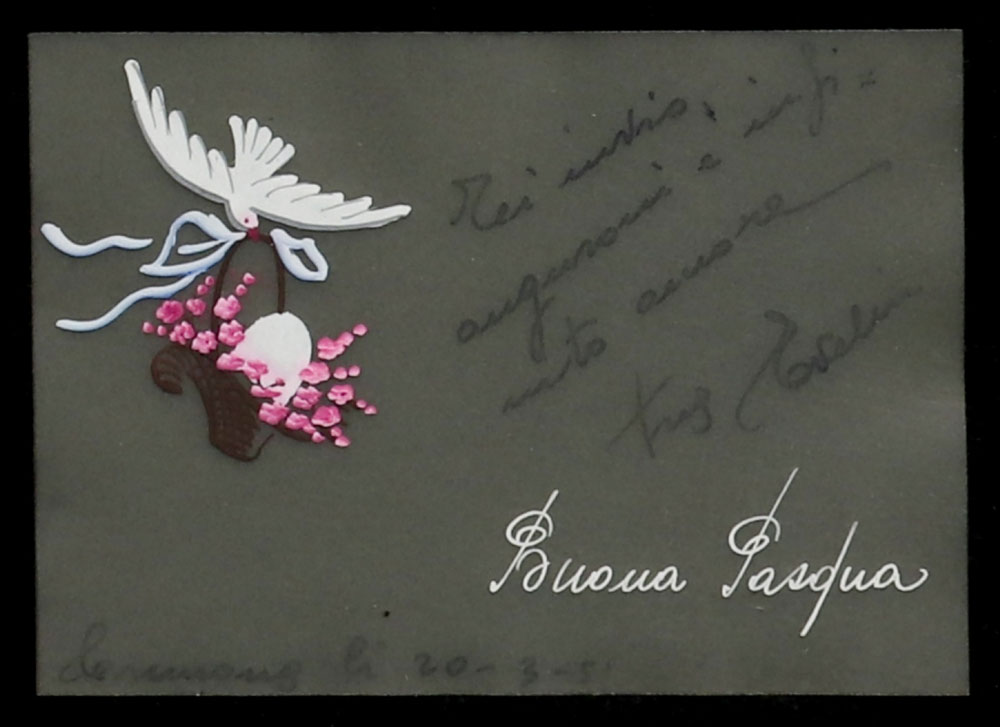

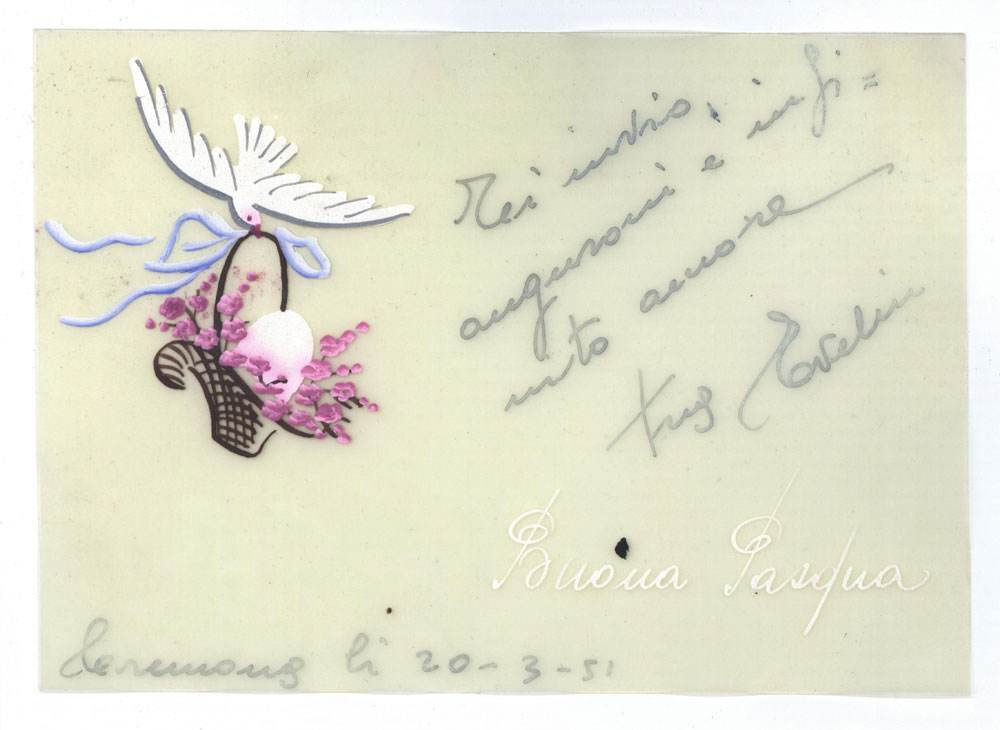

I think one of the ones you’re referring to might be the Easter card. [In the photo book] I just want to see their handwriting and what they’re saying to each other, so I didn’t [include the Easter card]. But I am glad that my mom especially sent a lot of postcards. That breaks up the collection in a way.

How does working with a conservator fit into this story?

During one of my many trips to St. Louis, we contacted [Conservator] Noah Smutz and brought the collection to him. He’s very, very experienced and was able to restore them, flatten them, and unfold them. [The letters were on] this very thin paper that was folded up, and back then they used different paper, especially in Europe. I don’t know if it was because of the weight of the airmail in that time. It took him about three and a half months to do, but he did a great job. He was actually the one that recommended Anderson Archival. He just said you guys know what you’re doing, and really, that’s what we needed.

So you connected with a conservator for the physical letters and you had a rough plan to create your photo book. How did Anderson Archival bridge the vision to the reality?

Well, I knew that I wanted a book of them. But you guys were able to really narrow it down to, ‘What kind of file do you want?’ So really [for] the digitization of the collection, you guys were very helpful. We decided to go with the JPEG form and definitely higher resolution because they’re kind of hard to read, some of them.

Another way that Anderson Archival helped was guiding us in how the files were organized. That was something that, I mean, it was like, ‘Do you want all the postcards in one folder?’ We wanted them in some sort of sequential order so that I could just pull them into the book.

Planning can be the trickiest part—aside from imaging itself, of course. Some of the translucent materials proved to be new challenges for our team.

I feel like you guys did a great job of doing that with the black background. It took a little bit of [emailing and approvals] back and forth, but not a whole lot. The timeliness was great. Everything was just a good experience.

Did working with Smutz during the conservation steps of the project help you find anything new about your collection?

I guess back then there weren’t zip codes. My mom would write ‘St. Louis, MO’ and then in parentheses write ’10.’ And I’m like, ‘What the heck is that? Like, did she make a mistake?’ But it’s the final two numbers of the zip code, because where my dad was, was 63110. The ‘10’ was the post office’s way, before they had zip codes, to identify where in St. Louis they were. I had no idea.

[The letters] had all been folded, and so they were curved, and they were not in any sort of order. They did a great job, my parents did, really preserving the sequence of these letters. They were very good about putting the day, the month, the year, the time of day, and the place. We literally brought the cigar box to Noah, and he kind of carefully opened it and saw what we had.

What’s it been like to share such a personal collection with experts like Smutz and our team?

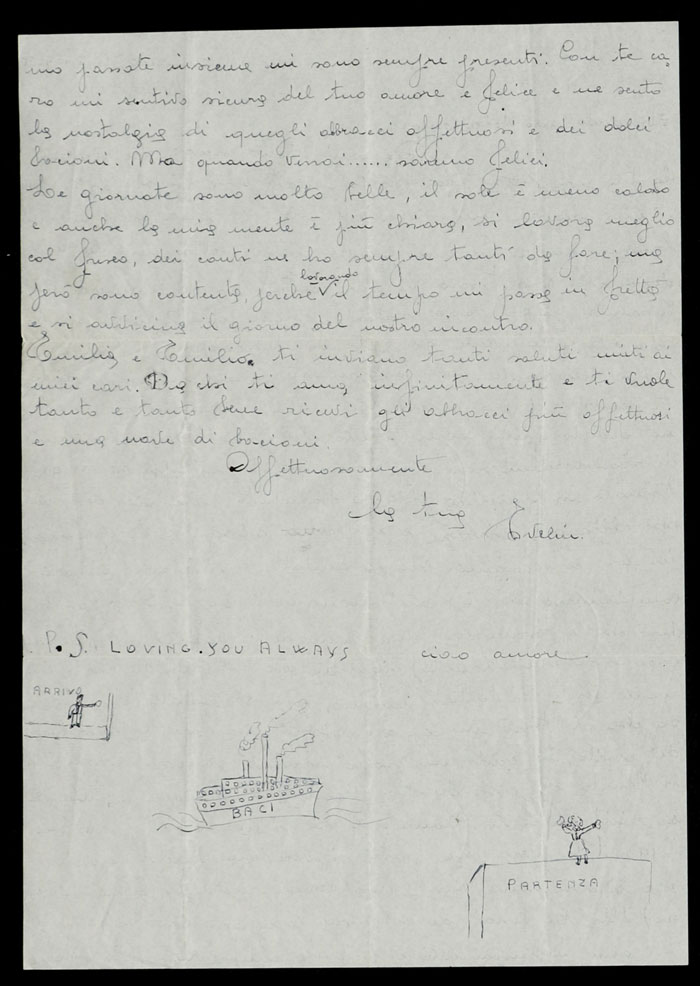

You know, going through them and reading some of them…I feel kind of like [I’m] reading somebody else’s mail, you know? But [my parents] were very sweet and tender with each other, loving words and stuff like that. It was very innocent, but just really special and very caring. Because they had the common family members, they kept tabs on each other’s family. My father was sending money back to Italy to help out his family.

Even just their salutations…I mean, you don’t have to know a whole lot of Italian [to understand]. But…my dad would throw in English [too], like [writing] ‘“Ti amo” that means “I love you” in English.’ This is very sweet.

What is it like to work on the photo book now that you have the collection conserved and digitized?

I’m very happy with it. The book is enormous, 11”x14”. This whole process, because I had to do them letter by letter, took probably about 10 to 15 hours of time. Now I think that because I know the layouts and how they look after getting the hard copy, I think it’ll take me a little bit less, maybe 10, for the other two. I’ve been able to break it up with their postcards, but I think in the next couple of volumes, I’ll add in more pictures of them when they were young and that sort of thing, just to mix it up a bit.

But it’s turning out really good. At first my middle sister was like, ‘Oh, I’m not interested in having a copy.’ But then she took a look at Volume One and was like, ‘No, I’ll take one.’ My kids want to look at them. They don’t read Italian right now, but it’s part of their history so I am happy that we are archiving them.

Was there anything else new that you discovered maybe about your family, or just about the collection itself, once you had the digitized files in front of you?

Like I said, I’m only [on] Volume One. I think I learn things every time I do this. I haven’t read every single letter, but I do try and read parts of every few. And that is, like I said before, it’s really emotional, and that I find things about them in their youth that, of course, I didn’t know. I think that’s super special and the reason why people should do things like this.

I was telling a friend about the collection, and she said she has letters that her uncle who was in the US Army wrote and she is putting together a book [with the original hard copies]. I was like, ‘Yeah, you should digitize everything, and then make this book,’ in order to preserve them instead of (or in addition to) just using the hard copies in a book. This way she can make multiple copies and share this part of her family history with her extended family members.

Have a vision for your collection that you’d like a little assistance bringing to life? Let’s talk. Call us today at 314.259.1900.